By Michele G. Moss, Johnson Moss Law

Introduction

This article discusses just a few of the many skilled African American scientists, mathematicians, inventors and engineers whose inventions and achievements still touch our everyday lives. Despite their prodigious achievements, their names remain hidden and largely unknown by most Americans. These African Americans, and countless more, should be celebrated and honored for their extraordinary contributions to this country and to the world. To this day, part of the struggle of African Americans in this country is to be seen as Americans and given proper credit for our accomplishments. These inventors and their amazing achievements are a part of American history. Let us shine a light on the achievements of these great Americans not only during Black History month, but all year round.

Garrett Augustus Morgan

Garrett Augustus Morgan was one of the most prominent African American inventors. He created not one, but two inventions that are still used in some form today: the safety hood (gas mask) and the three position traffic signal. Morgan was born on March 4, 1877, outside of Paris, Kentucky. He was the seventh of 11 children. In his mid-teens, Morgan moved to Cincinnati, Ohio to look for work. At the age of 16, he then moved to Cleveland, Ohio.

Garrett Augustus Morgan was one of the most prominent African American inventors. He created not one, but two inventions that are still used in some form today: the safety hood (gas mask) and the three position traffic signal. Morgan was born on March 4, 1877, outside of Paris, Kentucky. He was the seventh of 11 children. In his mid-teens, Morgan moved to Cincinnati, Ohio to look for work. At the age of 16, he then moved to Cleveland, Ohio.

Despite only having a sixth-grade education, Morgan was a mechanical genius and a born entrepreneur. He first worked in a textile factory and learned how the machines worked. He became so skilled at repairing and improving machines that he opened his own sewing machine repair shop in 1907. He also launched a clothing business with his wife, Mary Anne Hassek, a seamstress from Bavaria, and even branched out into cosmetic products, patenting the first chemical hair straightener.

Morgan became a wealthy man and was the first African American in Cleveland to own a car. He joined a new organization called the NAACP and donated money to Negro colleges. In 1920 he started an African American newspaper, The Cleveland Call, and opened an all-black country club.

Morgan’s Traffic Signal

After witnessing a traffic accident between a car and a buggy, Morgan decided that a device was needed to prevent, cars, buggies and pedestrians from colliding. Prior to his traffic signal, most traffic signals had only two positions: stop and go. These two position signals had no interval between the stop and go commands. As a result, collisions at busy intersections were common. Morgan’s traffic signal was mounted on a T-shaped pole, and had 3 different signals: stop, go and stop in all directions. The stop in all directions signal halted all traffic in all directions before vehicles were allowed to proceed. This delay made it less dangerous for motorists to travel through intersections and allowed pedestrians to cross the streets safely. On November 20, 1923, Morgan received a U.S. patent for his mechanical traffic signal. He also patented his traffic signal in Canada and Great Britain. Morgan eventually sold his patent to General Electric for $40,000.

The Safety Hood

Morgan created this invention after seeing firefighters struggling to breathe in the face of the thick smoke they encountered in the line of duty. In 1914, Morgan secured a patent for his device, a canvas hood with two tubes. Part of the device held on the back of the hood filtered smoke outward while cooling the air inside. Morgan’s safety hood was the prototype and the precursor for the gas masks used today, and was widely adopted in the North, where it was purchased by over 500 cities. He also sold his safety hood to the U.S. Navy and Army. The U.S. Army used a slightly redesigned version of his safety hood in World War I. However, sales of the safety hood in the segregated South were difficult. Demand for this device did not take off until 1916, when the city of Cleveland was drilling a new tunnel under Lake Erie for a fresh water supply. Workers drilling the tunnel hit a pocket of natural gas and there was an explosion that trapped the workers underground with toxic fumes. When Morgan heard about the explosion, he and his brother donned his safety hood to help rescue the trapped workers. Morgan and his brother saved two lives and recovered four bodies before the rescue effort was halted.

Sadly, despite the successful use of his safety hood, sales actually went down. As a result of his heroism, the public was now aware that he was African American and many refused to purchase his products. Adding insult to injury, Cleveland failed to fully recognize Morgan and his brother for their bravery. In addition, some Cleveland newspapers completely wrote Morgan and his brother out of the story and praised other men as the rescuers. Morgan was eventually recognized as a hero of the Lake Erie rescue by the city of Cleveland prior to his death on July 27, 1963. Morgan’s inventions saved countless lives and, in modified form, are still in use today.

The Hidden Figures: Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson

Katherine Johnson

Katherine Johnson was born in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia in 1918. Johnson, along with Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson, was one of the “Hidden Figures” that helped launch the first Americans into space.

Katherine Johnson was born in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia in 1918. Johnson, along with Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson, was one of the “Hidden Figures” that helped launch the first Americans into space.

Johnson’s brilliance with numbers was evident from an early age. Johnson was a high school freshman at 10 and graduated at 14. At 18, Johnson enrolled as a student at West Virginia State College, a Historically Black College and University (“HBCU”). Johnson graduated with honors with degrees in math and French and began teaching at a black public school in Virginia. Johnson and two men were chosen to be the first black students at West Virginia University in 1939. Johnson enrolled in the graduate math program, but left school at the end of the first session to start a family with her husband. After her three daughters got older, Johnson returned to teaching.

In 1952, a relative told her about open positions at the all-black (segregated) West Area Computing section at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics’ (“NACA”) Langley laboratory. The West Area Computing unit was a group of African American female mathematicians who were considered “human computers”, performing complex computations and analyzing data for aerospace engineers. The West Area Computing section was headed by Dorothy Vaughan. Johnson began work at Langley in 1953, although three years later her husband succumbed to cancer in December 1956.

NACA later became part of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (“NASA”). Johnson hand-computed the trajectory of the first manned launch in 1961 of Alan Shepard. Shepard was the first American in space. On February 20, 1962, John Glenn flew Friendship 7 to become the first American to orbit the earth. Before Glenn took flight, as part of his pre-flight preparations, he asked Johnson to double-check the math of the “new electronic” computations done by the computers that were used to determine his flight path. Johnson remembers Glenn saying “If she says they’re good, then I’m ready to go.” Glenn’s flight was a huge success and marked a turning point in the space race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

Johnson described her greatest achievement as the calculations that helped synch Project Apollo’s Lunar Module with the lunar-orbiting Command and Service Module. Johnson also worked on calculations for the space shuttle program. Johnson retired from NASA in 1986 after 33 years of service.

Johnson’s tremendous contributions to the space program were not recognized until many years after her retirement. In 2015, Johnson was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama. Johnson received the Silver Snoopy award from NASA in 2016, which goes to people who have made outstanding contributions to flight safety and mission success. Also in 2016, a $30 million, 40,000 square foot Computational Research Facility was renamed in her honor. Johnson passed away on February 24, 2020. On February 20, 2021, the 59th Anniversary of John Glenn’s historic mission, a Northrop Grumman Cygnus capsule named for her, the S.S. Katherine Johnson, was launched to resupply the International Space Station.

Dorothy Vaughan

Dorothy Vaughan (formerly Johnson) was born on September 20, 1910, in Kansas City, Missouri. Vaughan was a mathematician and computer programmer who became the first African American manager at NACA, which later became part of NASA. In 1917, her family moved from Missouri to West Virginia. Vaughan earned a degree in mathematics in 1929 from Wilberforce University near Xenia, Ohio.

Dorothy Vaughan (formerly Johnson) was born on September 20, 1910, in Kansas City, Missouri. Vaughan was a mathematician and computer programmer who became the first African American manager at NACA, which later became part of NASA. In 1917, her family moved from Missouri to West Virginia. Vaughan earned a degree in mathematics in 1929 from Wilberforce University near Xenia, Ohio.

Vaughan worked as a math teacher before she started working for NACA’s West Area Computing unit in 1943. The West Computers, as the women were known, provided data essential to the success of the U.S. Space program. The original supervisors of the West Computers were white. In 1949, Vaughan was promoted to lead the West Computers. Vaughan was the first African American supervisor at NACA and one of its few female supervisors.

Vaughan served as the head of the West Computers until 1958, when NACA was incorporated into NASA. As head of the West Computers, Vaughan also advocated for other (white) computers in other groups who deserved promotions and pay raises. At that time, the space program began using computers and Vaughan became an expert at FORTRAN, a computer programming language used for scientific and algebraic applications. Vaughan also contributed to the Scout Launch Vehicle Program. Vaughan sought but never received another management level position at NASA after serving as the head of the West Computers. Vaughan retired from NASA in 1971 and passed away on November 10, 2008. Vaughan’s legacy and contributions to the space program were not fully appreciated until after her death.

Mary Jackson

Mary Jackson (formerly Winston) was born April 9, 1921, in Hampton, Virginia. Jackson was a mathematician and aerospace engineer who became the first African American female engineer to work at NASA.

Mary Jackson (formerly Winston) was born April 9, 1921, in Hampton, Virginia. Jackson was a mathematician and aerospace engineer who became the first African American female engineer to work at NASA.

Jackson was raised in Hampton, Virginia, and graduated from high school with honors. She earned a dual degree in mathematics and physical science at the Hampton Institute, now Hampton University, in 1942. Jackson worked as a math teacher in Maryland for one year before returning to Hampton. She started working for NACA in 1951 as part of the West Computers. In 1953, Jackson left the West Computers to work for engineer Kazimierz Czarnecki, conducting experiments in a high-speed wind tunnel. Czarnecki suggested to Jackson that she enter a training program that would allow her to become an engineer. At the time, Virginia’s schools were still segregated and Jackson had to obtain special permission to take classes with white students. In 1958, Jackson became the first black female engineer at NASA.

Much of Jackson’s work at NASA centered on airflow around aircraft. Despite some early promotions, Jackson was denied management-level positions and left engineering in 1979. She took a demotion to become manager of the women’s program at NASA, where she sought to improve opportunities for all women at NASA. Jackson retired in 1985. Sadly, Jackson’s contributions to the space program were not fully recognized until after her death in 2005.

The Hidden Figures’ Legacy

In 2016, author Margot Lee Shetterly released her book, titled “Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race”. Shetterly’s book chronicles the amazing lives of Johnson, Vaughan, Jackson and Christine Darden, and their key roles behind some of America’s greatest achievements in space.

At the time Johnson, Vaughan and Jackson began working at NACA, the laboratory began hiring black women to meet the skyrocketing demand for processing aeronautical research data. Urgency and twenty-four hour shifts prevailed and they were required to work separately from their white female counterparts in an all-black group of female mathematicians. Jim Crow laws in effect at the time required all “colored” mathematicians to use separate bathrooms and dining facilities from white employees. Despite these harsh and humiliating conditions, the women of the West Computers distinguished themselves and developed a reputation for excellence. When NACA was incorporated into NASA in 1958, NASA closed the segregated facilities. At that time, Vaughan and many of the West Computers joined NASA’s Analysis and Computation Division, which was made up of men and women of all races.

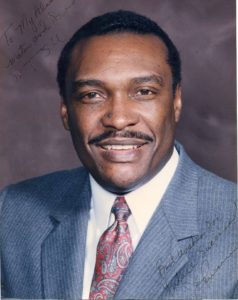

Jesse Eugene Russell

Jesse Eugene Russell was born in Nashville, Tennessee on April 26, 1948. Russell is known as the “Father of Digital Cellular Technology” based on his work on wireless networks and digital cellular technology. His childhood was spent in economically- and socially- deprived neighborhoods in the inner-city of Nashville. As a teenager, his focus was on athletics, not academics.

Jesse Eugene Russell was born in Nashville, Tennessee on April 26, 1948. Russell is known as the “Father of Digital Cellular Technology” based on his work on wireless networks and digital cellular technology. His childhood was spent in economically- and socially- deprived neighborhoods in the inner-city of Nashville. As a teenager, his focus was on athletics, not academics.

Russell’s life changed when he had the opportunity to attend a summer educational program at Fisk University. His attendance at this program sparked his interest in academics. He received his Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering (BSEE) from Tennessee State University in 1972. Russell earned his Master of Science in Electrical Engineering (MSEE) degree from Stanford University in 1973.

As a top student in the School of Engineering, Russell was the first person hired from a HBCU by A&T Bell Laboratories, today known as Bell Labs. As the chief digital architect for Bell Labs, Russell led the first team there to introduce digital cellular technology to the United States in 1988. Although his team accomplished this over 15 years after the first mobile phone call was made, that mobile call was over an analog system, not digital. Russell’s team developed the technology that transformed communications by using digital technology, creating “2G” for the “second generation” of mobile phone systems.

Russell rose through the ranks at Bell Labs and worked as Vice President of Advanced Communication Technologies, Vice President of Advanced Wireless Technology Laboratory, and Chief Wireless Architect of AT&T, among other positions.

Russell currently owns over 100 patents, including the invention of the first digital cellular base station and fiber optic microcell utilizing high power linear amplifier technology and digital modulation techniques. His invention of the digital cellular base station essentially changed the use of cell towers to transmit signals. His innovative work allowed the beginning of the digital cellular evolution, digital cellular standards, personal communications networks, as well as the emergence of “Mobile Cloud Computing” within 4G Broadband wireless networks.

Russell became the first African American in the U.S. to be selected as the Eta Kappa Nu Outstanding Young Electrical Engineer of the Year in 1980. Russell was inducted into the National Academy of Engineering in 1995 for his contributions. In 1992, he was named the U.S. Black Engineer of the Year for the best technical contributions in digital cellular and microcellular technology. Russell is a fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc., and served as a Board of Director Advisor for the Telecommunications Industry Association (“TIA”).

Russell is currently chairman and CEO of incNETWORKS, Inc., a New Jersey-based Broadband Wireless Communication Company focused on 4th Generation (4G) Broadband Wireless Communication Technologies, Networks and Services.

Closing

The achievements of these African Americans are even more astounding when we think about the barriers they had to overcome. The stories above show how difficult it was for African Americans to take graduate-level classes, advance in their careers, or to obtain proper credit for their work due to segregation and racism. The government and Jim Crow laws worked against these great Americans, but ultimately did not stop them from making important and long-lasting contributions to this nation. We are grateful for their perseverance and amazed at their success in the worst of conditions. Their indefatigable spirit is an inspiration to all of us.

Source Materials:

Garrett Augustus Morgan

1. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/theymadeamerica/whomade/morgan_hi.html

2. https://www.transportation.gov/connections/garrett-augustus-morgan-inventor-gas-mask-and-traffic-signal

3. https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Garrett_A._Morgan

4. https://www.biography.com/inventor/garrett-morgan

Katherine Johnson

1. https://blackamericaweb.com/2019/12/25/little-known-black-history-fact-hbcus-and-hidden-figures/

2. https://www.nasa.gov/content/katherine-johnson-biography

3. https://www.npr.org/2021/02/20/969790056/spacecraft-named-for-hidden-figures-mathematician-launches-from-virginia

4. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Katherine-Johnson-mathematician

Dorothy Vaughan

1. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Dorothy-Vaughan#ref1261405

2. https://www.nasa.gov/content/dorothy-vaughan-biography

Mary Jackson

1. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mary-Jackson-mathematician-and-engineer#ref1261403

2. https://www.nasa.gov/content/mary-w-jackson-biography

Jesse Eugene Russell

1. https://blackamericaweb.com/2020/02/21/little-known-black-history-fact-jesse-eugene-russell/

2. https://aaregistry.org/story/cell-phone-pioneer-jesse-russell-born/

3. https://connectednation.org/blog/2019/02/26/black-history-maker-in-technology-jesse-russell/

4. https://www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/jesse-russell-sr