By Matthew Akiba

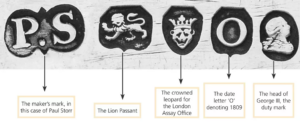

If you have ever bought jewelry, invested in a silver or gold bar, or inherited a family heirloom, you may have noticed that the precious metal is often stamped with intricate hallmarks. These hallmarks may indicate the purity of the precious metal, convey the year the article was manufactured, identify the maker of the article, identify the city where the article was manufactured, or identify the assay office where the article was tested for its purity and marked.

The concept of hallmarking precious metals is an early form of consumer protection. Indeed, the first signs of hallmarking precious metals dates back to nearly 400 AD and has been discovered on silver objects from the Byzantine period.[1]

Prior to applying for law school, I worked as a cataloguer for a South Florida auction house and spent a considerable amount of time straining my eyes through a small loop or magnifying glass to decipher these small hallmarks and to properly convey the approximate date, manufacturer, and origin of a particular item of jewelry, silver candelabras, or gold snuff boxes. It was not until I became a lawyer that I became interested in understanding what the implications of these hallmarks were under the law, and what regulations govern a manufacturer or retailer engaged in the sale of precious metals, such as silver, gold or platinum.

The 13th century Statute of Edward I provides an early example of consumer protection regulating the sale of precious metals:

No goldsmith… shall from henceforth make or cause to be made any manner of vessel, jewel or any other thing of gold or silver except it be of the true alloy and that no manner of vessel of silver depart out of the hands of the workers, until further, that it be marked with the leopard’s head.

Indeed, the leopard’s head is still used today as a hallmark to identify the London Assay office.

In 1906, the United States enacted its own legislation, governing and regulating the hallmarking of precious metals. This in turn blends an interesting, and often overlooked, convergence of consumer protection and trademark law. 15 U.S.C. §§ 291 et seq., often referred to as the “National Stamping Act,” makes it unlawful for any person—being a manufacturer of or wholesale or retail dealer in gold or silver—to import or export, or cause to be imported or exported or otherwise transported in interstate commerce—“any article of merchandise manufactured after June 13, 1907, and made in whole or in part of gold or silver, or any alloy of either of said metals, and having been stamped, branded, engraved, or printed thereon . . . any mark or word indicating or designed to indicate that the gold or silver or alloy of either of said metals in such article is of a greater degree of fineness than the actual fineness or quality of such gold, silver, or alloy, according to the standards and subject to the qualifications set forth in sections 295 and 296 of this title.”

The National Stamping Act goes on to provide that in the case of gold, the “actual fineness of such gold or alloy shall not be less by more than three one-thousandth parts than the fineness indicated by the mark stamped, branded, engraved, or printed upon any part of such article.” 15 U.S.C. § 295. In the case of silver, “the actual fineness of the silver or alloy thereof . . . shall not be less than more than four one-thousandth parts than the actual fineness of the silver or alloy thereof. . . ” Id. at § 296. That is, if you purchase a gold ring that is stamped “14K”, this indicates that the ring is composed of approximately 58.3% gold and 41.7% alloy. As such, the actual fineness of the gold in the ring shall not be less than more than three one-thousandths of 58.3% gold. If your grandmother’s silver serving bowl that you inherited is stamped “sterling” this indicates that the bowl is approximately 92.5% pure silver and the remaining 7.5% is metal alloy—typically copper. As such, the actual fineness of the silver bowl shall not be less than more than four one-thousandths of 92.5% pure silver.

Interestingly, the National Stamping Act implicates an often-overlooked aspect of trademark law. More specifically, 15 U.S.C. §297 mandates that whenever any person who is a manufacturer or dealer subject to Section 294 of the Act applies or causes to be applied any mark on an article “any quality mark or stamp indicating or purporting to indicate that such article is made in whole or in part of gold or silver or of any alloy of either metal” such person shall:

- apply or cause to be applied to that article a trademark of such persons, which has been duly registered or applied for registration under the laws of the United States within thirty days after an article bearing the trademark is placed in commerce or imported into the United States, or the name of such person; and

- if such article of merchandise is composed of two or more parts which are complete in themselves but which are not identical in quality, and any one of such parts bears such a quality mark or stamp, apply or cause to be applied to each other part of that article of merchandise a quality mark or stamp of like pattern and size disclosing the quality of that other part.

Finally, an important aspect of the National Stamping Act is that it creates a private cause of action, entitling “[a]ny competitor, customer, or competitor of a customer of any person in violation of [the Act], or any subsequent purchaser of an article of merchandise which has been the subject of violation” to bring suit for injunctive relief and for damages in any United States District Court in which the defendant resides or has an agent, “without respect to the amount in controversy.” 15 U.S.C. §298(b) (emphasis added). Further, the Act provides for the recovery of costs, including reasonable attorneys’ fees in bringing the action. Id.

The same holds true for “any duly organized and existing jewelry trade association[s]” who may sue as the real party in interest. Id. at §298(c).

As the title suggests, “[a]ll that glitters is not gold.” If you or your clients have purchased an article that was believed to have a certain silver or gold composition but is suspected to have been falsely marked as to that article’s gold or silver composition, remedies which are often overlooked are available, in the form of injunctive relief, damages, and attorneys’ fees.

[1] https://www.silver-editions.co.uk/blog/product-news/history-of-hallmarking_1.htm.